Study Finds Racial and Gender Inequities in Education Leadership Pipeline

Across the nation, school districts have emphasized the importance of racial and gender diversity among its educational leaders. Yet, during the 2011–2012 school year, only 20 percent of all principals were non-White, despite an increasingly diverse teacher workforce and a new emphasis on culturally responsive pedagogy.

Who is promoted from assistant principal to principal? How long do promotions tend to take, and in what contexts do promotions occur? With specific attention to race and gender, Lauren Bailes, assistant professor in the University of Delaware School of Education, and co-author Sarah Guthery at Texas A&M University–Commerce answer these questions in their new study, “Held Down and Held Back: Systematically Delayed Principal Promotions by Race and Gender.”

Using data from the Texas Education Agency, Bailes and Guthery analyzed the probability of and time to promotion for over 4,000 assistant principals in Texas from 2001 to 2017. While principal promotion processes vary by district, assistant principals in the study had earned a master’s degree and acquired a principal’s license, satisfying the minimum qualifications for promotion to principal in the state.

Bailes and Guthery found that a candidate’s race and gender significantly and inequitably affected their promotions. Their study revealed that Black and female assistant principals were systematically delayed and denied promotion to principal in comparison to their White or male counterparts, even though these candidates had equivalent qualifications and more experience on average.

“We are optimistic that superintendents can take action based on these findings and take some initiative to determine whether similar patterns exist in their districts,” said Bailes. “These kinds of analyses can tell us so much about where talent exists in a system, where it gets squeezed out of the leadership pipeline, and how to address those inequities.”

Racial and gender inequities early in the path to promotion

While previous research has identified racial and gender inequities at the top levels of education leadership, Bailes and Guthery’s study is unique in its focus on the candidate’s path to promotion. The authors focus on time to and the probability of promotion once an individual has self-selected into the leadership track. This focus allowed the authors to identify racial and gender inequities much earlier in the education leadership pipeline.

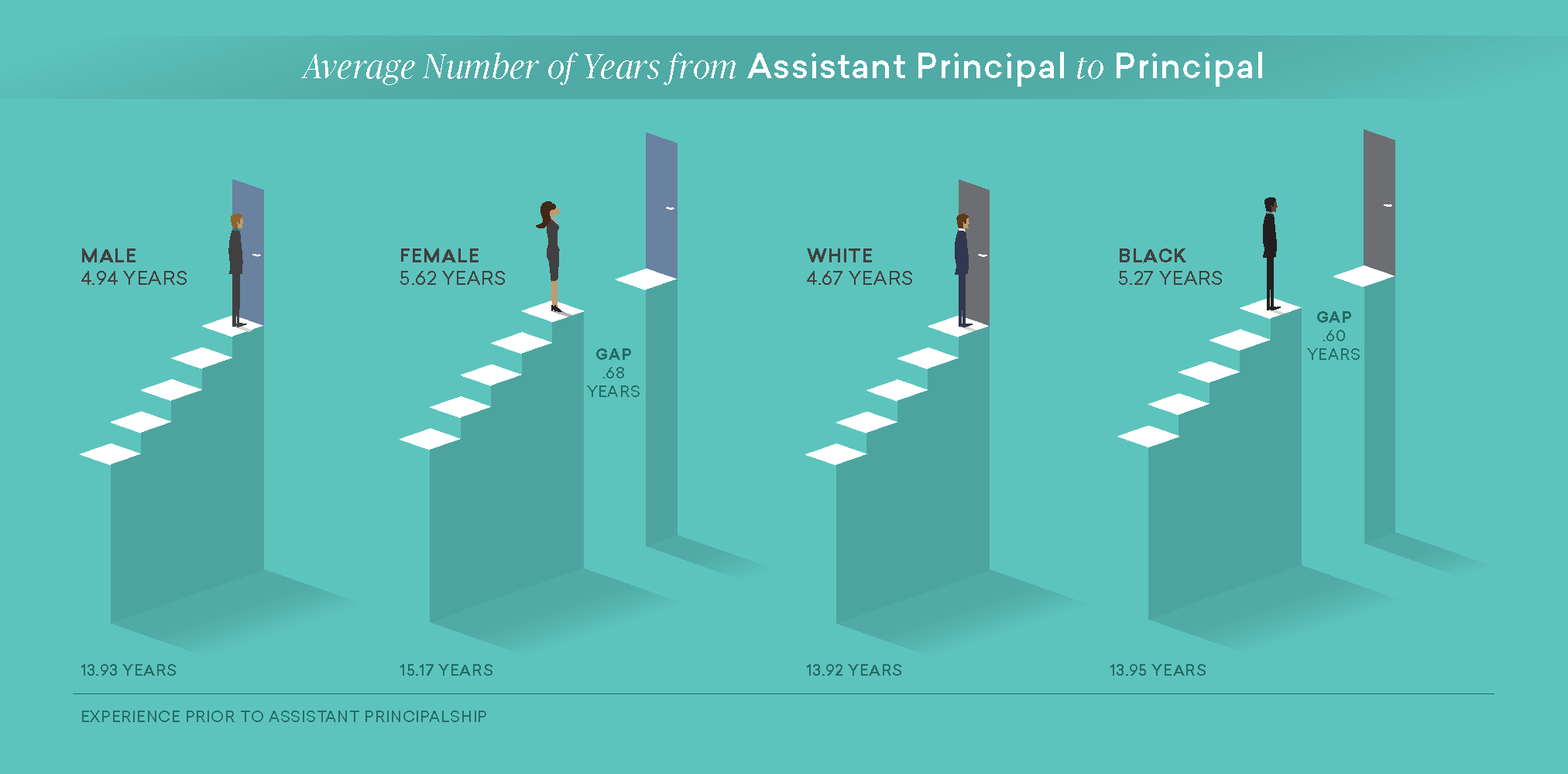

For example, after accounting for variables like education, experience, school level, and school location, Bailes and Guthery found that Black assistant principals were 18 percent less likely to be promoted than equally-qualified White candidates. Further, they found that the average time to promotion for Black candidates was 5.27 years. In comparison, the average time to promotion for their White peers was 4.67 years.

Bailes and Guthery also discovered gender inequities specifically among high school principalships. Even though half of all high school assistant principals in Texas were women, these candidates were 5 to 7 percent less likely than their male peers to be promoted. Surprisingly, as women gained more years of experience in their assistant principal roles, the likelihood of their promotion decreased relative to their male peers.

Much like their analysis of Black candidates’ path to promotion, Bailes and Guthery also found that women who were promoted waited longer than their male counterparts. On average, women served 5.62 years as high school assistant principals, while men served only 4.94 years on average.

“At every point of promotion, the pool of candidates is whiter and more male, especially compared to the teacher workforce,” said Guthery. “We find that diversity exists in the pipeline, but the pipeline tends to squeeze out women and Blacks much earlier than studies of school leadership usually capture.”

These gaps in promotion time are especially concerning, since Bailes and Guthery found that women and Black candidates had more years of experience before becoming assistant principals than their male or White peers. On average, men began high school assistant principal roles with 1.25 fewer years of experience than their female peers. The study highlighted an even larger gap of 1.62 years of experience among men and women in elementary and middle school principalships.

In addition to promotion time, Bailes and Guthery identified another barrier that women faced in their path to high school principal. After examining women’s promotions across elementary, middle, and high schools, the authors found that women were more likely to be promoted to principal in elementary schools than in high schools. This difference in promotion likelihood remained even when those candidates had more career experience and worked as assistant principals in high schools for longer periods than their male peers.

“Because a high school principalship is so often viewed as requisite for district leadership, women who lead elementary schools are less likely to be tapped for superintendencies and other district leadership positions,” said Bailes.

Implications and recommendations

Bailes and Guthery’s findings illustrate systemic barriers to promotion for Black and female principal candidates, which ultimately affect Black and female teachers and students throughout the entire school system.

“Because principals and district leaders are more likely to identify educators of their own race for promotion, the underrepresentation of minority groups is likely to ripple throughout schools and districts,” said Bailes. “Prior research also shows that hiring more Black principals can help close the achievement gaps between White and non-White students nationally.”

Given the findings of their study, the authors encourage state and district policymakers to use equity in promotion as one way of rating school success or quality. At present, equity in promotion is not part of many states’ criteria for healthy schools.

“Administrators, such as principals and district leaders, need to identify and actively nurture diversity in all levels of leadership,” Bailes said. “It is crucial that districts monitor inequities in their promotion practices.”

View video with co-authors Lauren Bailes and Sarah Guthery

Article by Jessica Henderson

Graphic and video courtesy of the American Educational Research Association